Completely made of brass (although some rare specimens of wood have been preserved), and with a number of keys ranging from 9 to 12, the Ophicleide was invented around 1814 by Jean Hilaire Asté (aka Halary). The instrument was first premiered to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1817 and to the patent office in 1819. In 1821, Labbaye Jr. patented a removable version, with one more key (10) and a tuning-slide in the lead pipe. In the 1840s Adolphe Sax had the great idea of changing the mouthpiece for a clarinet reed to create the first saxophone prototypes. The most common figures are in C and B flat, but there are also high ophicleides in F and E flat (called Quinticlaves) and even a contrabass version in F or E flat.

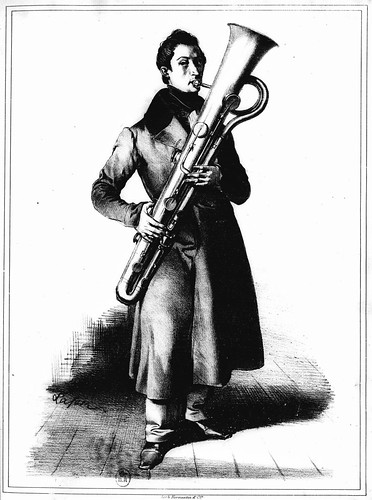

Completely made of brass (although some rare specimens of wood have been preserved), and with a number of keys ranging from 9 to 12, the Ophicleide was invented around 1814 by Jean Hilaire Asté (aka Halary). The instrument was first premiered to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1817 and to the patent office in 1819. In 1821, Labbaye Jr. patented a removable version, with one more key (10) and a tuning-slide in the lead pipe. In the 1840s Adolphe Sax had the great idea of changing the mouthpiece for a clarinet reed to create the first saxophone prototypes. The most common figures are in C and B flat, but there are also high ophicleides in F and E flat (called Quinticlaves) and even a contrabass version in F or E flat.The name ophicleide literally reffers to “key serpent” (from the Greek ophis-serpent and kleis-key), and it gives us clues about the reason why this instrument was invented: to replace the serpent and facilitate instrumental play and tuning by the exclusive design of keys. The awkward holes of the serpent at its not-really-satisfying sound production are gone. In many cases, the ophicleide will replace the serpent both in church and in its role as the bass part of the band.

Similarly, it found widespread use within the orchestra, being the opera Olympie by G. Spontini (1819) the first work to contain it. There is some really extensive literature for the instrument, for both orchestral and windband settings, as well as chamber music repertoire (mainly theme-and-variations with piano), and a large number of original methods, many of which include an extensive collection of duets in their final part.